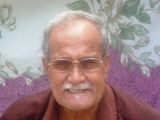

Our Matriarch - Grandmother Kautakarawa

My parents lived in the village of Rawannawi at the western side of the island near the site where ships anchored when they called at Marakei. My father had built a small and humble thatched ‘uma’ very close to the beach where the waves pounding on the outer reef edge played a constant rhythm of moving sound to our ears.

Our grandmother, Nei Kautakarawa (arouser of heaven), came and visited us occasionally and both Tony and I would relish the moments that we shared with her during her visits. The moment of her arrival would find us running in circles around her, holding her hand and nabbing at her grass skirt, trying to get her attention. We clamoured to get her favour and would not stop until she said a word or did something that would placate our need for approval.

Her presence overshadowed the proximity of our parents and our need for them. We hungered for our grandmother’s affection and her slightest approval of us signalled the achievement of some unsurpassed feat on our part. Her approval meant everything and we strived hard to get it. She had no respite from us even when she laid down to relax, for no sooner had she stretched herself face down on the mat than we pounced on her back and started bouncing up and down, pulling at her long, curly, greying hairs and gleefully laughing and shouting all the while. We were oblivious of the fact they she may have only wanted to lie down quietly on her own and relax.

All we wanted was to have fun with her while she was with us and jumping up and down on her back was one of our favourites. We adored and loved our grandmother, and it was thus an exceedingly sad day when we heard wailings and shouts coming from the direction of our parents’ thatched ‘uma’ as Tony and I walked back from our usual frolicking on the beach. Amidst all the commotion, fuss, crying and grieving, we were told by our mother that Nei Kautakarawa had passed away.

At first we could not grasp the meaning of her words. “Why, what happened?”, I asked. “I don’t know,” our mother replied. “Your father said she didn’t wake up from her sleep” “What will happen next?”, I asked. “She is going to be buried in the earth”, replied mother. Tony and I were absolutely shattered. Our grandmother was gone! One minute she was with us and in an instant, she wasn’t there. The chorus of cries of farewells mingled with grief coming from our relatives and friends added to our sense of loss and brought home the reality that we had indeed lost our beloved grandmother. She had departed this world and had gone to the ‘other’ side

. “Tia bo Nei Kautakarawa!” (Farewell Kautakarawa!). Tony and I cried our eyes out. As we stood there shuddering with uncontrollable sobs, looking at our dear grandmother rolled up in a woven mat besides her dug grave, we both realized that we would never see, feel or touch her again. For me, it was a complete loss and fresh tears welled up in my eyes until they dribbled over my face, mouth and down on my bare chest.

For the next few days I walked aimlessly alone on the beach, sometimes alone, at other times with my brother, as though trying to recall a lost past, but in reality, we were struggling to forget and let go of the past - the lingering remembrance of our grandmother.

After our parents left Marakei, Tony and I fell into the clutches of traditional practice. It was customary (and still is) that the firstborn child, whether a son or daughter, was assigned to the father’s family and he or she would be named after one of the family’s elders or ancestors of whichever gender. The second child was assisgned to the mother’s side with the same naming ritual. The custom proved fortuitous in the case of my elder brother and I because not long after the death of our grandmother, my parents had to leave for Ocean Island, an island formed from a raised coral platform as a result of movements in the earth’s crust and located about 200 miles in an approximate SSW direction of our island.

Ocean Island was to be home for my parents for the next two or three years. Children weren’t allowed to accompany their parents to the island as it was administered by Britain and was designated as a closed district. My father’s name was Tatireta and my mother’s name was Tiraoi but after they married, it changed to Annie Tatireta. From what I was told, my father had been recruited to Ocean Island to work as a ‘caretaker’ for Mr. Greene, the Manager of the British Phosphate Commissioners on the island (I never did learn of his surname). The BPC was a consortium of British, Australian and New Zealand interests which had been given a charter to mine phosphate on two islands, Ocean Island and Nauru. The BPC recruited labourers from the nearby islands of the Gilbert Islands, (now Kiribati), the Ellice islands (Tuvalu) and Chinese from Hong Kong.

I didn’t know the actual year when my parents departed for Ocean Island but I do know that when they left, my older brother Tekeang (later changed to Tony) and I were left on Marakei while Philomena our sister and Gerard, the fourth in the family, accompanied them to Ocean Island. Protocol dictated that only two children were allowed to accompany their parents. The traditional custom of our people immediately took over and I found myself placed under the care of our mother’s family who lived in the village of Rawannawi, while Tony was whisked off to the village of Norauea where our father’s relatives lived. These were to be our new homes for the next two or three years (To be continued…………)